I'd like to start by acknowledging the Traditional Owners of the land we are meeting on today–the Ngunnawal people–and I pay my respects to their elders, past, present and emerging and extend those respects to First Nations people here with us in the room today.

Introduction

I'd also like to thank Innes [Willox] and Brent [Ferguson] who keep asking me back to the Policy-Influence-Reform forum, and it is wonderful to share the stage with Dr Anna Cody and Mary Wooldridge. To complete the triad, I'm going to be talking about some women's issues, which may or may not be what you're expecting.

I also want to start by acknowledging and congratulating your very own Megan Lilly for [her] appointment that was announced this morning, as Deputy Jobs and Skills Australia Commissioner. A very worthy appointment, and we're very pleased to have her. Your loss, I'm sure, is very much our gain.

I also want to thank all of people in this room. It's been a busy time for workplace relations and human resources practitioners, (and I understand Brent had a slide yesterday that really reinforced – to you all – how much of a busy time it's been!)

Reforms to the Fair Work Act do not end with the assent of those Acts.

We all know that.

You might expect me to comment on the work my Department is doing to implement the new laws, drafting regulations and codes, and sitting down with more consultation with people like your good selves.

Or, you might expect me to observe the critical work of the Fair Work agencies, and you've already heard from them about work they're doing, providing guidance, kicking off proceedings and the like.

But, how can I not also acknowledge the good work of people like you in this room? The people who continue to show up to our consultations in spite of us having so many things to consult on, to review and provide feedback on our material. Participating in those important Fair Work Commission proceedings to make sure that the evidence the Commission needs to make good decisions is there, right in front of them.

Also– thank you for what is your core job – advising businesses on how to respond to and comply with the laws.

You are as much part of the system as any of us, and I thank you for all the work you do every day, for the expertise and passion that you bring to helping the system work, including through times of change.

Cultural change

To switch up a little, I'm not going to talk any more about that. All of those are things we're grappling with together at the moment.

Those were things that we've known were coming in the pipeline, [such as] election commitments and the like.

Then there are the things you just can't quite plan for.

I reckon you've probably already spent a little bit of time talking about the Government's approach to responding to the allegations about criminal infiltration in the bargaining processes and the behaviour of CFMEU officials and delegates in association with that conduct.

I reckon you've spent some time talking about the CFMEU. Yes?

How could you not?

It's a dominating piece of industrial relations news at the moment, and it's evolving in real time before us as we see applications from the General Manager of the Fair Work Commission – unprecedented – to appoint an administrator to vacate all of the positions in a union.

We also see other regulators being called upon to do their side of things–[the] Fair Work Ombudsman and police–having been specifically requested by Ministers to respond to these allegations.

And while many of our minds in these sorts of circumstances, including mine, go to what is the appropriate legislative policy, regulatory and enforcement response – to these diabolical scenarios we're hearing about – it also goes to something else.

It goes to culture.

While on our various screens and feeds we've been seeing all this material, and our lawyer and advisory brains are of course going off. What do we do about this, how do we respond? I also find myself thinking… “who would want to work in the construction sector?”

If you're a young person right now in your final years of school, would you embark on an apprenticeship in construction, given what we've heard?

What woman would want to work in a workplace like the ones we've been hearing about?

Why should anybody be asked to put up with that?

Culture in this industry has been a talking point for a while. Underneath the long‑standing back and forth and the politics and the headlines, about [whether] we need a Building Regulator, what sort of enforcement response do we need, Royal Commissions, and whatever else.

There have been people who have been very much focused on the culture and the cultural change that it might take to make the sector more inclusive, including and specifically for women.

This was raised by several participants at the Jobs and Skills Summit, and some of those contributions specifically advocated for the Government to do more to back in industry‑led work that was already underway, including the Australian Contractors Association.

I remember Michael Wright from the ETU talking about the dire need for more electricians and saying, "What if we had a whole other gender to draw on?". Because about 2 per cent of electricians are women, and we need 32,000 more of them by 2030 to meet our clean energy targets. (I say this every speech.)

The Government did respond. They created the National Construction Industry forum in the Fair Work Act to enable a forum through which the Government could work with industry and support a sustainable, inclusive and safe sector.

Yet, when it comes to creating a sector that is inclusive of women, we might have a bit of a road ahead of us.

Are women welcome in the construction industry?

Female employment share

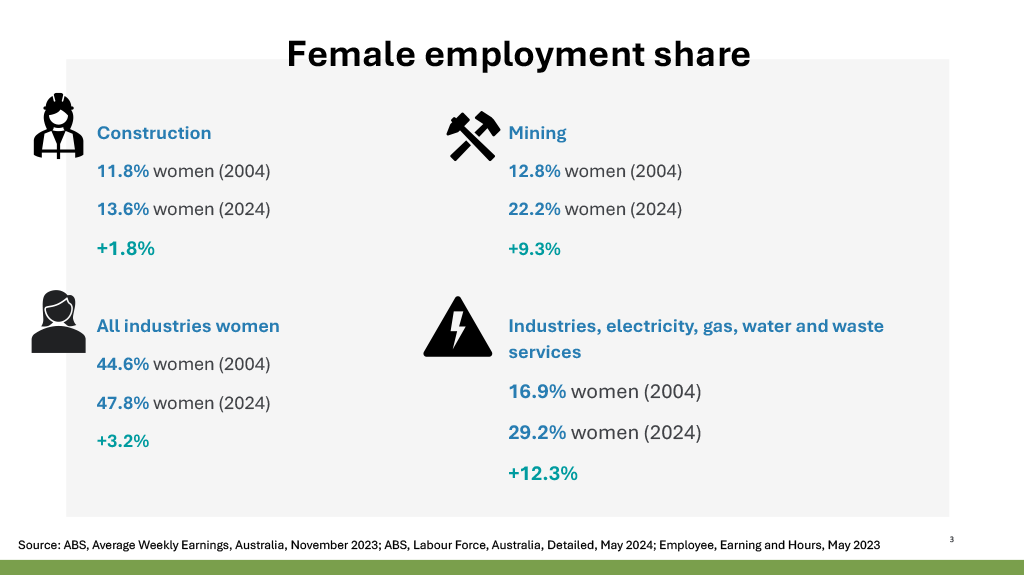

The starting point is very low.

Only 13.6 per cent of employees in the construction sector are women. It's the lowest of all industries – that's not a good league table to be heading up. That 13.6 per cent includes not just the tradies, but all the admin and payroll workers as well [who are] more traditionally equal or feminised. I don't have the figure here, of how many actual tradies in the sector are women, but it will be less than 13.6 per cent.

And in 20 years we've moved the dial a massive 1.8 per cent!

That's not very much.

I asked for some comparators just last night, and we see across all industries, women's participation has gone up 3.2 per cent.

Then you look at some other male‑dominated industries, and [while there are some] bigger leaps as you might expect, construction is now the lowest bar.

The data tells us a story, one that we might be a bit uncomfortable with, but we need to pay attention to it. I acknowledge the work of Mary Wooldridge, CEO of the Workplace Gender Equality Agency, because she has also been shining a light on data that may be making some people feel uncomfortable as a result.

I think it's imperative we work together, Government and industry, to make a concerted effort to move the dial faster on these numbers. Not just because it's the right thing to do to make these higher‑paying sector jobs more accessible to women, but because, as someone at my dinner table said last night, diversity in our teams brings a huge amount of value, different ways of thinking and different perspectives, that we need in any team and any workplace.

And perhaps more urgently, because we need to meet our skills requirements for that sector and all sectors into the future, we need to make these jobs appeal to all genders.

Skills shortages and gender imbalance in our labour market

Construction isn't alone in experiencing skills shortages in our labour market. And we're really seeing the impact of the gender segregated labour market on skills shortages. Occupations that are forecast to grow are also often quite skewed towards one or other of the genders.

I'm going to borrow from the excellent work of Jobs and Skills Australia and show you some more data that reinforces this.

Occupations experiencing shortage and strong gender imbalance

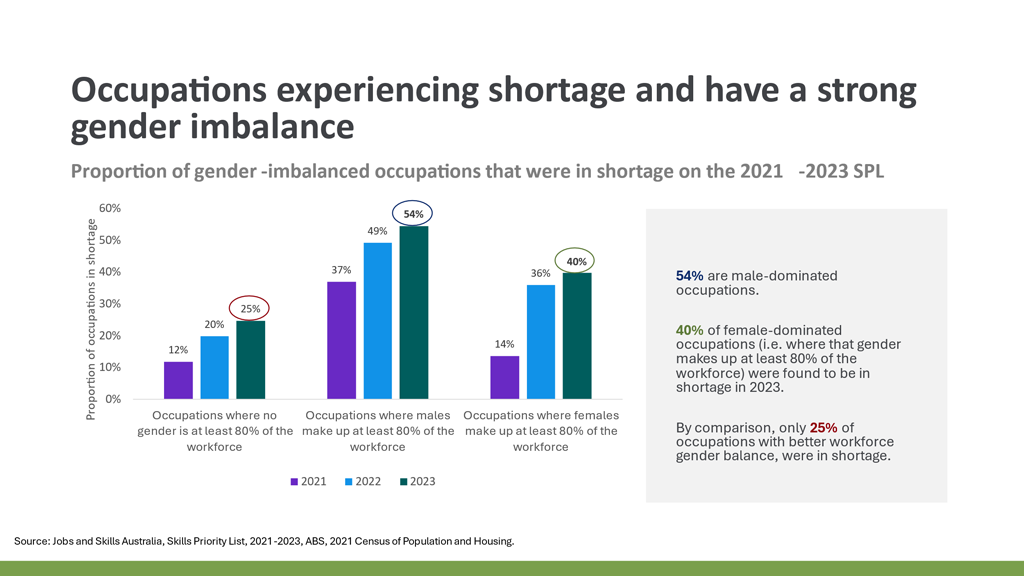

Professor Barney Glover, the Jobs and Skills Australia Commissioner, presented this slide just last week at another forum we both spoke at, that shows the impact of gender‑skewed occupations and the relationship between that and skills shortages over the last three years.

The first set of columns is about occupations where there might still be a gender imbalance, but it is under the 80 per cent threshold shown by Jobs and Skills Australia. You can see that skills shortages are going up, but overall the numbers are much lower than when you move over to the male‑dominated occupations where you see an increase [in skills shortages], since 2021, from 37 per cent to 54 per cent.

On the final set of columns, we see the female‑dominated sectors, where we see a similar pattern. The numbers are lower, but look at that jump from 2021 to 2023 in the female‑dominated sectors? The care sectors are also the ones that are growing. I like to consider, "Do you want someone there to switch the machine off when you're lying in a hospital bed?"

We're going to need more men in nursing and childcare, and we're going to need more women in construction and mining, in order to meet the requirements we need in the future.

We've got work to do across a number of fronts, and I ask, what's behind that data? What's behind those graphs?

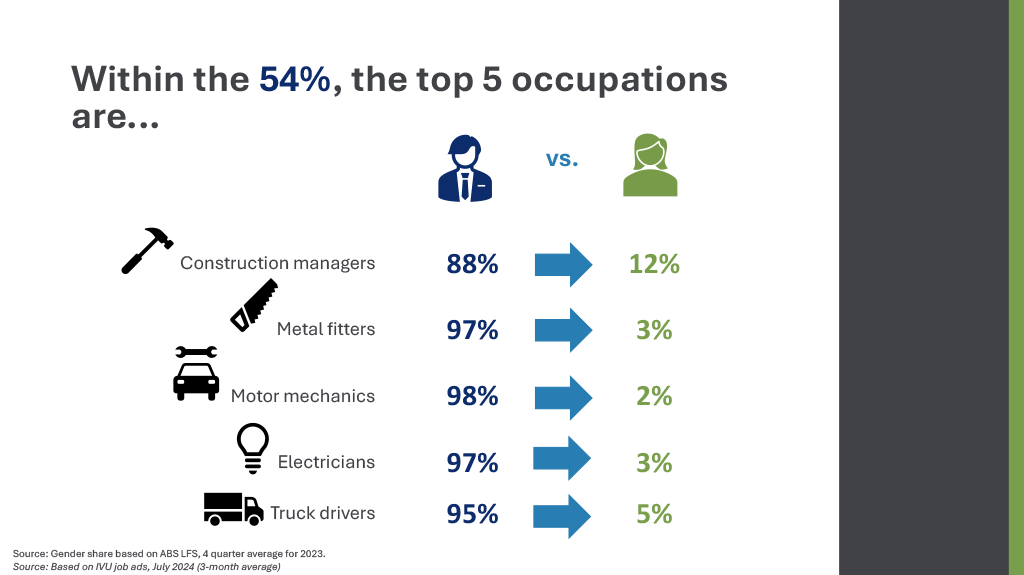

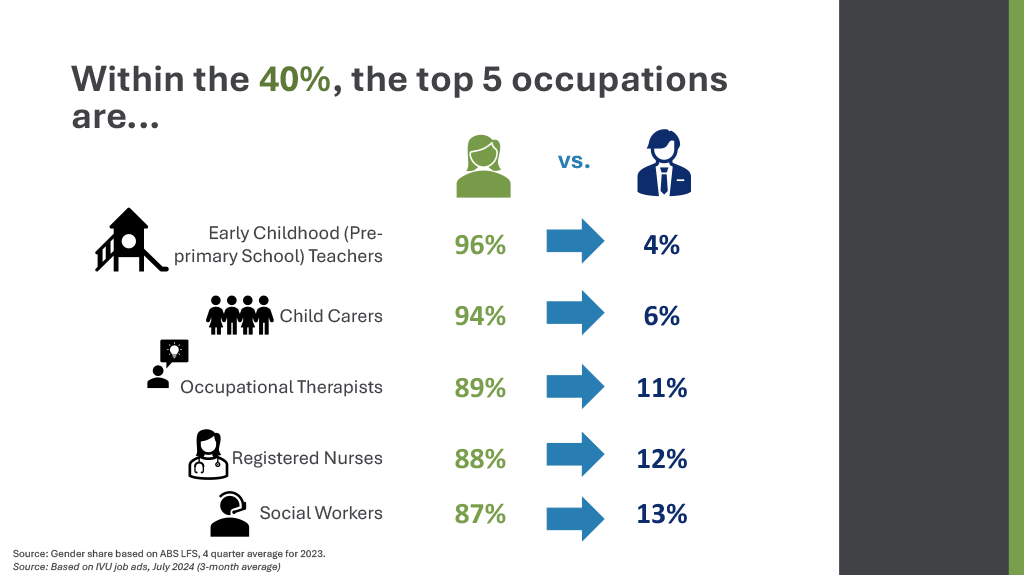

These are the top five male‑dominated occupations with skills shortages. There's some interesting things in there, but it's noteworthy that construction managers sits at the very top.

Electricians is more gender‑skewed than construction managers. And here we have the flip side, the women, and no surprises there. There's the social workers, child carers and nurses.

Reasons for gender imbalances

Now we might hypothesise a whole range of reasons for these gender imbalances, but I think it's undeniable that female‑dominated sectors tend to be lower paid and generally more award reliant.

This is why the Government's using a range of levers to support these workforces grow and attract the skilled workers they need.

For example, like legislative levers and funding levers –you would have seen the announcement from last Friday about the Government funding childcare wages, and it's a really important announcement. It will flow higher wages through to childcare workers, and part of the conditionality of that is not raising fees so we don't have another participation issue with fees going up – [such as] parents not being able to afford fees, taking their kids out of childcare.

There’s more work to do structurally on childcare, and I think you'll see a lot of work in the system on the childcare sector.

You've seen that the Government has prioritised a number of measures, and in my space, making gender equality a clear object of wage setting in the Fair Work Commission.

The Fair Work Commission is currently, and very methodically, identifying and working with parties to correct gender disadvantage built into award wages. Like, commissioning research, having hearings, which many of you are probably a part of and I thank you for that work.

Without you we – and they – won't be able to get that balance right. Clearly it’s a historical legacy piece, and an important piece to correct, now we've got the legislative mechanisms and the will.

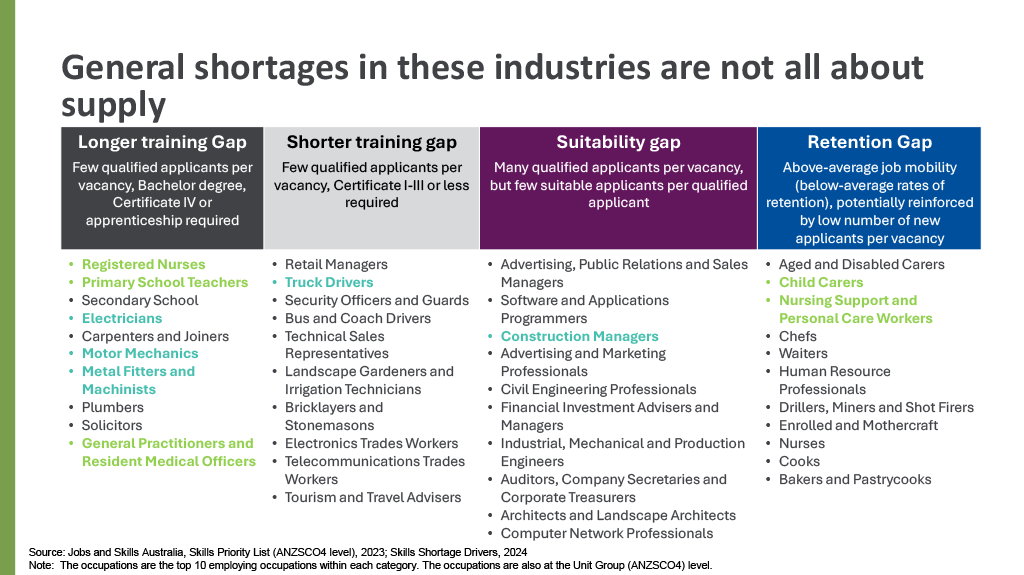

Training, retention and suitability gaps

We tend to start with [the idea], that if we don't have workers, it's because we don't have enough workers in the country. And then we have a debate about immigration and a bunch of other things. Insufficient supply and demand is certainly a factor, but there are other reasons.

The other thing that is interesting, is that Jobs and Skills Australia is doing work on the question of, where you have shortages of labour, what is the reason for that?

Jobs and Skills Australia has looked at four components, and a couple of them relate to training. We all know that to get skilled electricians, you need to train them and to train them you need people coming out of the school system who can do maths and want to be an electrician and are prepared to enter an apprenticeship. There's a whole bunch of issues around that. We've got a review of apprenticeship incentives underway at the moment.

The parts I found really interesting were the suitability and retention gaps. The suitability gap refers to having people with the qualifications, who for some reason are not suitable. That means they're lacking in something else. Maybe they are someone from a migrant background whose English isn't great. Or someone who doesn't have a certain sort of skill.

What we've done here on the slide is highlighted some of the sectors that happen to also be gender‑skewed.

You can see – on the training gap side of things – there's quite a few gendered occupations in that list, but also the suitability gap. Construction managers there. One of the reasons we don't have enough Construction managers is not necessarily not having enough qualified people. [In this example], the suitability gap is at play.

Another gap I find really interesting is the retention gap. This is about where there are enough workers. You're not hanging on to them. And when I look at the list I think, "Why aren't they hanging on to child carers, nursing workers, chefs, waiters?" It might be something to do with their pay, conditions and treatment in the workforce.

I was Fair Work Ombudsman for five years, and spent a lot of time looking at underpayment of wages and bad treatment of chefs in hospitality.

There’s more work to come from Jobs and Skills Australia, but you can see how the data really shines a light on these issues and gives us lots to reflect on and think about.

Looking ahead

What do we do about all of this? It was a stroke of genius putting the person I sat next to at my table last night. We spent a lot of time talking about these issues – of attracting women into the construction sector – in particular from the perspective of me having been a regulator and enforcer, and her an obviously very excellent human resources manager with long experience working in this sector.

One of the things we talked about – and something I became aware of when I was at Deloitte –was some pioneering work done to trial the five-day working week in construction.

This is something many of us take for granted. We can have an argument about the new laws around the right to disconnect, and other things another time, but a five‑day working week is not the norm on many commercial construction sites in this country.

Project 5 was a research project undertaken by academics and funded by Roberts Co and Health Infrastructure New South Wales. The then CEO of Roberts Co, Alison Mirams, is really passionate about getting more women into construction. They won a tender with the New South Wales Government to build the Concord Hospital Redevelopment, using a schedule of only working weekdays, enabling workers to have weekends.

The outcomes were transformative.

These mostly men were able to spend the weekend – the full weekend – with their families; doing the Saturday soccer run, recovering, relaxing, helping their partners with the child wrangling, or perhaps just giving their partners a break, maybe enabling their partners to work. Their partners reported huge improvements to their wellbeing, their relationships, and it was described as life‑changing.

I've seen video footage of the workers and their families interviewed. It is quite striking, the impact this one extra day, has had.

Importantly, the project was finished on time and on budget.

Something to work with there perhaps? I know there's some long‑running incentives, including of current workers’, to perhaps not have a five‑day work week because the overtime on a Saturday and Sunday is appealing. That's the culture challenge, and a leadership challenge, for all of us.

The Construction Industry Culture Taskforce, which is an industry‑led initiative led by the Australian Constructors Association along with some State Governments have released a draft culture standard for the industry. The proposed theme is ‘Time for Life’ which is based on a target of construction workers working fewer than 50 hours a week, with no workers working more than 55 hours a week. So, ensuring that all workers work the equivalent of no more than five days per week. This is currently being piloted.

Now at my table last night, there was some other conversations about unpaid leave, that many women or parents take in association with childcaring, and how superannuation doesn't apply to unpaid leave.

Now we know the Government's announced superannuation will be paid, [to] Government funded parental leave, from 1 July 2025. There's also other unpaid leave and leave outside of this is taken in association with caring for children that super would apply to – something to think about there in terms of how to mitigate the economic detriment that arises for workers taking time out to care for children, which obviously has a significant impact on women's earnings and retirement savings.

There are a range of other things we might do at a workplace level, and I'm sure many of you are doing them, to support women's participation in the workplace.

Going back to childcare, and how expensive it is in this country and the ways this can inhibit women from returning to work after having children. Often financially, the numbers just don't add up to go back to work. And how might employers in the regulatory framework better mitigate the impact of this? We know the Government has making childcare more accessible on its radar – it's a big priority for the Government, and I reference the funding of increases to wages. But there's no doubt that there might be other things that could be done at the workplace level.

I learnt today, following up on my conversation last night, if you have a childcare centre on your work site, apparently you get a fringe benefits tax exemption. Unfortunately, if you're working in construction, I'm pretty sure that's not a good place for a childcare centre – a construction site.

So, if you wanted to support childcare by funding the childcare places – not on your work site – then the fringe benefits tax might be the killer.

I have had some informal conversations with people about this and I’ll continue to explore it.

These are the things we might all think about.

Enterprise bargaining is a key tool that can enable business to deliver better‑tailored conditions for the women you all employ.

We monitor enterprise bargaining in my department. We code them in a database, and there are a number of clauses that have had a big uptake over the last decade or so.

Paid parental leave provisions, for example, have gone from 17.1 per cent to 23.7 per cent in the last ten years (2013 to 2023). That's a solid increase.

Breast feeding breaks, are also up from 1.7 per cent to 10.3 per cent. That's a big uplift.

The increase in the number of agreements with childcare provisions, has gone from 1.7 per cent to 10.3 per cent.

Finally, the portion of agreements containing gender equality provisions – a broad term that encapsulates a few things – [shows] a massive leap from 1.9 per cent, basically 2 per cent, to a touch over 20 per cent.

You, industry, are responding to the opportunity to put into agreements things that essentially make them more family friendly and boost women's workplace participation.

You've heard Ministers emphasise the importance of getting bargaining moving again, and some of the reforms of the last two years have been targeted to do just that. I know you don't love all the agreement making changes, but we have started to see that shift come through in the system.

There are a number of skills initiatives that my department has, that are designed to uplift the number of women working in traditionally male careers.

I’ll briefly mention the Australian Skills Guarantee, which is about getting more apprentices and trainees onto work sites and as a sub‑set of that data, [includes] targets around women. The targets are incremental and are set with a lot of consultation. We wanted to be ambitious but realistic about those targets.

We've also been working on consultation for a new program, Building Women's Careers, a $55.6 million program. I thank the Australian Industry Group for your submission into our consultation process. [Building Women’s Careers] is designed to enable Government to work with industry to really experiment – to pilot ways of getting the right culture and workplace environment to attract and support women in male‑dominated trades.

As I wrap up, I reflect on the fact that I spoke to you a year ago at this forum. You might recall I talked about this Government's commitment to tripartism.

To go back to where I started, tripartism only works when all the parties who are coming to the table do so in good faith, representing the interests of their constituencies, and most important, operating lawfully.

The Government is absolutely resolved to do what it needs to do to address what we've been presented with in recent weeks. To address the culture and conduct of the CFMEU, and anybody else who's been involved in unlawful conduct in the construction sector.

We are all going to need to work together to achieve this. And we must. If we don't, we won't have a sustainable productive, safe and compliant building sector working for all of us to deliver the houses and infrastructure we need as a community, now and into the future.

Thank you.